Cook's Portrait Fee

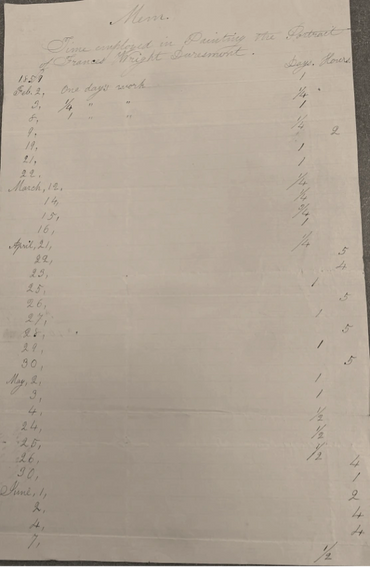

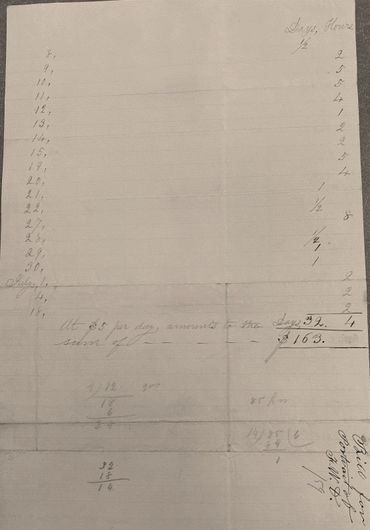

Nelson Cook’s posthumous 1859 portrait of Frances “Fanny” Wright D’Arusmont is unique among the over 200 Cook portraits the caretakers of this site have found since the site’s creation in 2003. To date, this is the only portrait for which there is a detailed accounting in Cook’s own hand of the time needed to complete the painting and the subsequent value the artist placed on the portrait. This accounting is shown below. We don’t know the exact amount Cook ever received for the painting – the amount written in pen just below Cook’s daily accounting says $163, but the amount he’s written in pencil in the lower right-hand corner just under where Cook has written “Bill for Portrait of F.W.D” reads $159. Is this an indication the artist cut the buyer a $4 deal? While the painting has still not been located by the caretakers of the Cook site, and while there is no specific record of the painting having been sold, a letter written by Cook may give us some clues as to its eventual disposition.

In a letter from NYC in May, 1860, Cook writes: "I have varnished Madame D'uresmond's portrait. Mr. Rose helped me hang it up, in a good light. It is at once recognized." Given the date of this letter, which was written 10 months after the artist painted his portrait of feminist Frances “Fanny” Wright D’Arusmont, it appears Cook has misspelled the name of his former posthumous subject. Cook’s reference to “Mr. Rose” in his letter also makes perfect sense since this in all likelihood is William E. Rose, who along with his wife Ernestine, was heavily involved in the woman’s suffrage movement. The Roses had great admiration for Frances D’Arusmont, who was a trailblazer for women’s rights during the first half of the 19th century.

We also know that Cook did the two Rose portraits about a year before Cook painted Frances. Could it be that Mr. Rose was the individual who commissioned Cook to do Frances’s posthumous 1859 portrait? Why then does Cook not connect Mr. Rose to the portrait until nearly a year later? Did it take that long for Cook to personally transport the painting to NYC from where the artist wrote his letter? Or perhaps Cook painted Frances purely as a speculative venture, and a year later Mr. Rose agreed to buy the portrait from Cook at the artist’s urging.

We’ll never know which scenario actually occurred, but in either case, it's more than likely the location Mr. Rose helped the artist hang the painting was in the Roses’s very own house in NYC, perhaps in the same room where Cook’s likenesses of William and Ernestine were hung.

For a number of reasons, the day-by-day accounting shown above is not necessarily an indication of Cook’s standard timeframe and fee to paint a portrait in 1859 – near the mid-point of his career. These factors include the following:

· Posthumous vs. Real Life Portrait: Many questions are at play here – perhaps more questions than definitive answers. Did this posthumous rendering of Frances Wright require Cook to invest more or less time to paint? Since Frances had been dead for seven years at the time Cook did her portrait, was he in no hurry to complete it? Expressed another way, had Frances still been alive and Cook painted her as a real-time sitter, would the artist have been more compelled to complete the portrait in a more-timely manner -- would Cook normally have taken less than five months to complete a portrait of a living sitter?

Since Cook painted Frances from an existing c. 1852 lithograph, would Cook have needed less time (less than 32 equivalent days) to complete the portrait than if the artist had started from scratch? After all, Cook only needed to copy a grayscale lithograph of the sitter to create a color oil painting. Or would Cook have taken an uncharacteristically longer time (both in terms of the 32 equivalent days and the 5+ months duration) to complete Frances’s posthumous portrait because the artist was only painting Frances between other commissioned works at the time? The logistics of remixing the necessary paints and other similar factors specific to Frances’s rendering with each of the 50 revisits Cook made to her portrait would suggest perhaps a longer timeframe was required than had the artist painted the portrait straight through.

Since the caretakers of this site have found only two Cook portraits from 1859 (Frances’s and one other), it may be that Cook took on the Frances posthumous project because 1859 was an especially slow year for the artist. But, of course, this is purely conjecture on our part. It also would be helpful to know if someone (William Rose?) actually commissioned Cook to paint Frances’s portrait. Or did the artist paint Frances simply on speculation and kept an accounting and assigned a price only in the event he would find an unknown buyer at some future date? We know that on at least several occasions Cook’s sitters failed to pay the artist for their portraits because they didn’t care for the likeness Cook created. This becomes a non-factor with a non-commissioned, posthumous portrait – the sitter is in no position to refuse payment.

We probably will never know the precise answers to these many questions, but to varying degrees they all played a role in the value Cook placed on his 1859 posthumous portrait of Frances Wright. That said, it’s hard to imagine Cook would have taken so long to complete a commissioned portrait of a living sitter – at the rate of 32 days per painting, Cook would have completed only about 11 portraits a year, which seems unlikely.

· Sitter’s Pose: Portrait sitter poses fall into 4 categories: bust (head & shoulders), half-length (from the waist up), ¾-length (from the mid-thigh up), and full-length (entire body). Generally, the artist’s price increases as more of the sitter’s body is shown – a full-length portrait would cost much more than a bust. Since human hands tend to be the most difficult body parts for most artists to portray, the presence of one or both hands in a portrait generally will increase the price. Based on these guidelines, Frances’s portrait is a half-length with one visible hand, which was fairly typical of Cook’s paintings during the 1850s. Consequently, in all likelihood Cook’s pricing for Frances’s portrait would not have been adjusted up or down due to her pose. Interestingly, Cook deviated from Frances’s ¾-length pose with two exposed hands depicted in the original lithograph. One wonders if this was a concerted attempt by Cook to keep down his asking price.

· Canvas Size: As a very general rule, the smaller the canvas, the lower the asking price. And the sitter’s pose usually dictated the portrait’s canvas size. Generally speaking, a bust would require a smaller canvas than a full-length portrait. However, a more detailed rendering of a sitter’s facial expression and a greater attention to detail of the sitter’s clothing and accessories might very well garner a higher price. We don’t know the size of Frances’s canvas, so it’s difficult to assess what role this played in Cook’s pricing. But compared to other Cook portrait busts from the late 1850s, Frances’s rendering appears less detailed [See Helen Freeman].

· Sitter’s Location: Cook’s hometown was Saratoga Springs, where the artist spent approximately half of his 60+ year career. The other 30 years were spent in Canada and in a number of New York state locations outside of Saratoga Springs: Rochester, Buffalo, Syracuse, Rome, Troy and New York City. From his letters to brother Ransom, we know Cook claimed to be doing better than some of his competitors. Yet the artist regularly sought to borrow funds from Ransom to make ends meet. The only specific references Cook ever made in his letters regarding his portrait fees were in the early 1850s while he was painting in Rochester: In 1854 a head & shoulders bust of a child cost $35; an adult bust: $50; a full portrait: $70 or more. Nelson also told Ransom he earned only $1,817 in a 22-month period between 1851 and 1853 while in Rochester. For context, we also know rent for his Rochester studios cost Cook $75 annually, but his other Rochester living expenses are unavailable to us. Cook’s inscription on the back of Frances’s portrait says it was painted in Saratoga Springs. At $163, his amount is considerably higher than the general Rochester fees Cook sited in his letter to Ransom only 3 years before. What accounted for this increase? Certainly, some of the increase may be attributed to Frances’s notoriety. But all other factors being equal, it’s very likely Cook charged less in Rochester than he did in Saratoga Springs, where he was better known and appreciated as a favorite son, and where the cost of living may have been higher.

· Foreground and Background Embellishments: Many of Cook’s portraits include a foreground and/or a background. The foreground may have consisted of a desk with items displayed which were pertinent to the sitter’s life. Or in some cases, the sitter is depicted holding a book or document(s) important to the sitter’s lifetime achievements. A typical Cook background employed elements such as the sitter’s chair, a drapery, an architectural column, and/or a distant view out a window. The presence and extent of these artistic embellishments generally would have increased the price of the finished portrait accordingly. Since Cook’s painting of Frances contains no foreground or background elements, the artist’s asking price would not have been adjusted upward to take these compositional additions into account. Once again, Cook has deviated from the original lithograph by opting to paint Frances without any of the lithographer’s compositional foreground elements, which probably would have reduced Cook’s fee to some minor extent.

· Intangibles: As noted above, it is unknown if Cook’s posthumous portrait of Frances was a commissioned piece or merely done by Cook on speculation. Knowing this might help us determine if Cook’s $5 per day fee was his standard charge. While purely speculative, for a commissioned work of a living subject it may be that Cook charged an amount commiserate with his sitter’s ability to pay. Cook may have felt justified in charging a more premium price to a more well-heeled sitter. Conversely, a non-commissioned, posthumous portrait painted by Cook purely on speculation may have been priced somewhat below his going rate, especially when worked on only when time allowed between other portraits.