Preserving Nelson Cook's Legacy

Nelson Cook's known portraits span a period of 60 years from 1830 to 1890 -- a portrait painted at the mid-point of his career is now in excess of 165 years old. It's difficult to know exactly how prolific the artist was during those 60 years, but since 2003 over 200 Cook paintings have been identified by this site's caretakers. This is certainly only a sampling of the artist's total production, especially considering that Cook was known to have used lower-quality art materials, which would have struggled to outlive the test of time. As such, in addition to the many paintings that were no doubt destroyed over the years by disinterested / uncaring future owners or by natural disaster, a host of others have succumbed to gradual deterioration beyond the point of many owners' financial resources to professionally restore them, which today can easily run $3,000 to $6,000.

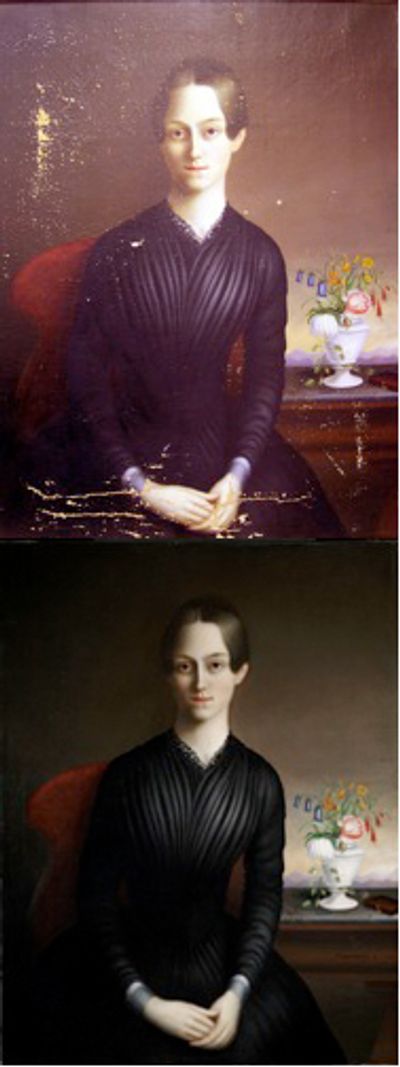

But fortunately, thanks to the foresight of dozens of the artist's portrait holders, Nelson Cook's legacy has been preserved for many years to come. One such example is the 2008 conservation of Cook's 1848 "Portrait of a Lady," which is shown on the right before and after preservation. This special section will show the restoration process this wonderful portrait underwent to ensure it could be enjoyed and studied by future generations.

Background

In 2004 "Portrait of a Lady" (1848) was donated to the New York State Museum in Albany, NY as part of the Bailey-Deyo Family Collection. The portrait is oil on canvas and measures 39" X 30". The painting depicts a young woman in a state of melancholy, and although the sitter is not noted by Cook as part of the artist's verso inscription, the caretaker of this site feels she may be Charity ("Cherry") Bailey whose 7-week old daughter Ruby died in March 1848, the same year as the portrait. In contrast, the portrait's restorer believes this may be a post-mortem depiction of an unknown sitter. We may never know which theory is correct. But what we do know is that at the time of donation the painting suffered from extreme flaking of the underlying ground and surface-level paint layers and was in need of a major preservation. The portrait was restored in 2008 by Ana Alba while she was a graduate student at the highly-regarded Buffalo State College Art Conservation Department. Special thanks are due Ana and Buffalo State College for providing us access to Ana's in-depth paper documenting her step-by-step conservation efforts and to the New York State Museum for granting us permission to highlight Ana's restoration process here.

Initial Examination Findings

Upon her initial examination of the painting, Ms. Alba made the following observation about the portrait's original workmanship: "As evident by the careful depiction of Portrait of a Lady and other examples of [Cook's] work, it is obvious he had an eye for detail and paid careful attention to the characteristics of the sitter." Although the portrait had been minimally treated some years before as part of an earlier restoration, when first examined at Buffalo State it was determined the painting's deterioration had not yet stabilized and was progressing further. In addition to lower-quality materials used by Cook, stains on the back of the portrait (Figure 1) indicated the painting had suffered from severe water damage and long-term storage in an area of high humidity.

Figure 1

It was also found that during the previous conservation effort the portrait was not relined, which is commonly done to help support an aging and unstable canvas. The wooden stretcher appeared to be original to the painting and despite its age maintained the painting's planarity in all but a few areas, notably the portrait's upper and lower right-hand corners which had distortions and dents. Due to all these factors, the ground coating used to prepare the canvas for painting was actively cleaving from the brittle, dirty surface, leading to widespread losses, which in turn produced cracking and lifting paint. As indicated by Figure 2, using ultraviolet radiation these losses were especially noticeable to the left of the sitter's head and across the bottom of the portrait where the water staining was most harmful. Surface crackling also was apparent along the left side of the sitter's face and neck where Cook had used darker paint to create shading. And one small canvas puncture was noted in the upper left-hand corner of the painting. Additionally, fly specks (waste material from flying insects) were present throughout the portrait. Cook had also brushed on a natural resin varnish to the painting's surface, which had yellowed due to age. Interestingly, although Cook was known to have selectively applied varnish to at least two of his paintings in an effort to enhance the visual shading depth of his sitter's body and face, the artist did not employ this particular technique when painting Portrait of a Lady.

Figure 2

It was customary in nineteenth century portraiture to use wilted flowers as a symbol of death and mourning. It was apt then that Cook included wilted flowers in his Portrait of a Lady, which clearly depicts a woman in a moment of somber melancholy. But what's interesting, as indicated in Figure 3, when examined using an infrared light, Cook's flower vase appears to have been originally painted as a lidded urn. Look carefully at the infrared image on the right and you can clearly see the urn's lid just below the flowers' stems. Either Cook himself had second thoughts about depicting a funerary urn in his portrait and changed this element to a vase of flowers, or the Bailey family asked the artist to make the change upon seeing Cook's original rendering.

Figure 3

Treatment Procedure

The first phase of treatment was to stabilize the portrait's flaking to prevent further paint loss as the painting was handled during the restoration process. This was accomplished by consolidating the most severe areas of paint loss with the use of warmed isinglass, a substance derived from fish swim bladders. The isinglass serves as an adhesive and is applied with a brush underneath each loose paint flake. Once cool, the isinglass is warmed again with a heated tool, and the adhesive flows under the paint layer and into the canvas, securing each paint flake in the process. Although this procedure proved successful, it also caused blanching of the varnish. Because of the painting's sensitivity to the heat and isinglass, this treatment was only used selectively. The paint losses in the remaining areas of the portrait were consolidated with the use of diluted BEVA 371, an adhesive solution that can be applied cold (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Once paint consolidation was completed, synthetic varnish was sprayed on the portrait to serve as a barrier layer. Next, it was necessary to further stabilize the flaking paint using a process called "facing," which temporarily secures any loose paint particles and protects the paint surface during conservation. First, four varnish coats were applied to the portrait's surface, rotating the painting 90 degrees with each treatment to be certain application was even. Then, using wheat starch paste and wet tissue paper, the painting was faced (see Figure 5) and once the paste had dried, three additional coats of synthetic varnish were applied.

Figure 5

When the varnish had dried, the stretcher was removed and the back of the canvas vacuumed to remove accumulated dirt. The portrait's tacking margins were flattened out using pressure and humidification and the painting was then attached to a temporary, working stretcher using special adhesive strips (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

To ensure adhesion between the ground and canvas layers of paint, a diluted solution of Beva 371 was applied to the back of the painting with a small roller. Since the portrait was still attached to the working stretcher, boards were placed below the painting to support the canvas during the rolling process (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

It was now time to remove the facing. In doing so several areas of paint stuck to the facing and were pulled away from the portrait. Reattaching these paint flakes required that a liquid solution of Beva 371 be applied to the areas of loss. Once dry, each missing flake was placed into proper position and a heat spatula was utilized to reattach the flakes to the painting's surface (see Figure 8). It was then necessary to soften the remaining facing prior to removal with deionized water. The entire surface of the portrait was then cleaned to remove any remnants of barrier varnish.

Figure 8

In the areas of most severe flaking and damage, surface cupping was still present from the previous humidification process. The hot table was heated to 130 degrees to soften the paint so that it could be more easily reattached to the canvas. A heated spatula again was used to flatten the raised cupping during this process (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

After localized tests showed the painting was extremely dirty, the entire portrait was cleaned using a special solution. Unexpectedly, the cleaned surface became dulled and a white, cloudy haze remained. This can be seen in Figure 10 in contrast to the area just to the right of the sitter's head, which had not yet been cleaned. Further tests determined that this hazy film would not be at all detrimental to the painting's surface appearance once the final varnish layer was applied. As such, no further treatment was required to return the portrait to its original luster.

Figure 10

The painting was now ready for varnish. First, the portrait was restretched on its original stretcher. Varnish was initially applied only selectively to undersaturated areas of the painting. Then, the entire surface was varnished by brush. To remedy the many tiny paint losses, a paintable fill was selected and tested on a piece of canvas with a weave similar to the original 160 year-old canvas. Trial applications determined the thickness needed to adequately fill the areas of missing paint and appropriate pigment tones were used to match the original paint colors. Figure 11 shows the portrait during this final inpainting procedure.

Thanks to Ana Alba's efforts, Nelson Cook's Portrait of a Lady was successfully restored and returned to the New York State Museum in 2008 where it was put on permanent display. And now for the rest of Ana's story...

After leaving the State University of New York at Buffalo State College with her Masters Degree and Certificate of Advanced Study in Art Conservation, Ana interned at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C. and at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT. She also was the William R. Leisher Fellow of Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Paintings at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Additionally, Ana also was later employed by Luca Bonetti Corp., a private conservation practice in New York City. In November 2014 Ana founded Alba Art Conservation in Pittsburgh, PA where she offers a wide array of painting preservation services to the greater Western Pennsylvania and Western New York areas. She also provides freelance work in New York City.

Figure 11